11 Monetary Inflation Correction and Calibration

So our model is basically calculated in dimensionless "points". Because currency is purely nominal, whether dollars, rubles, euros or pounds, or points, it makes no difference. Except the multiplication by a conversion factor c. To convert the values calculated in points in latest monetary data, it is necessary to determine this conversion factor. Here are some considerations necessary. Trivially, we would begin:

![]() and

and ![]() (11.1)

(11.1)

with the conversion constants

![]() (11.2)

(11.2)

This leads to no useful result,

because the time-dependent inflation is absent, and the final value is nominal

too small then (the relative numbers but remain unaffected). The GDP Y is fundamentally

affected by its growth![]() , but

additionally there is the nominal effect of inflation

, but

additionally there is the nominal effect of inflation![]() too, as GDP is

calculated in units of currency. This just looks natural on the capital stock

K, which is in addition but in contrast to GDP, effected by the interest rate

too, as GDP is

calculated in units of currency. This just looks natural on the capital stock

K, which is in addition but in contrast to GDP, effected by the interest rate![]() . This last

effect25 is of course fully contained in our

computation. What makes inflation so mathematically, is to convert the

conversion constant

. This last

effect25 is of course fully contained in our

computation. What makes inflation so mathematically, is to convert the

conversion constant![]() into a

time-dependent variable

into a

time-dependent variable![]() . Thus the scores

of Y and K have to be converted into monetary units by defining and computing

the additional effect of inflation.

. Thus the scores

of Y and K have to be converted into monetary units by defining and computing

the additional effect of inflation.

There are several possibilities to do this. The most elegant method would be now, of course, with the inflation calculated analytically. This is indeed possible but as it is far from trivial, it will been explained later in this book. The second possibility would be to use the statistical official rate of inflation , which is derived from the evaluation of a shopping basket. However, among those already described, and unfortunately very serious, limitations which can not give good results. Until we can calculate analytically the actual inflation rate, so we must be content with the simplest possible approximations. There are again several possibilities. First, trivially, but now with a time dependence c:

![]() and

and ![]() (11.3)

(11.3)

and with the conversion functions

![]() and

and ![]() ?? (11.4).

?? (11.4).

Such an approach is ruled out, however, because it is "through the chest from behind through the eye". For one then incorporates into the model the real values, where they should not be for model consistency. Better, and model-theoretically justified, is a simple linear approximation. The ratio V of points is determined by the total nominal GDP in currency and capital stock at the beginning

![]() (11.5)

(11.5)

and at the end

![]() (11.6)

(11.6)

of the integration, and one linearly interpolates the intermediate values:

![]() (11.7)

(11.7)

The model values in currency units are obtained in this case then as

![]() (11.8 a)

(11.8 a)

and

![]() (11.8 b)

(11.8 b)

which are now functions with the same linear conversion factor correctly are provided both to Y and K. In the above plot we see the two functions on the approach (11.4) and the approach to (11.8) of the correction function V in comparison.

Why is the ratio![]() approximately

linear growing at all, as one should expect naive that inflation and capital

cuts out in the quotient

approximately

linear growing at all, as one should expect naive that inflation and capital

cuts out in the quotient![]() ?

The reason is that capital is not degraded, but very probably the GDP, which is

very well subject to depreciation. But now what is the reason for the relative

linearity in the increase in capital ratio? Let us consider again our basic

equation simplified, and that without integrating them. Even then you will

already recognize many basic properties and relationships. We therefore take

simply the ratio of capital productivity from our formula (3.3):

?

The reason is that capital is not degraded, but very probably the GDP, which is

very well subject to depreciation. But now what is the reason for the relative

linearity in the increase in capital ratio? Let us consider again our basic

equation simplified, and that without integrating them. Even then you will

already recognize many basic properties and relationships. We therefore take

simply the ratio of capital productivity from our formula (3.3):

(11.9)

(11.9)

Now the coefficient of capital productivity is not identical to the rate of inflation, but it is closely related to it. For if the growth of capital does not equal to the GDP growth, inflation or deflation is then to be expected. Therefore, where a(t) is our exponential prefactor, rules:

![]() (11.10)

(11.10)

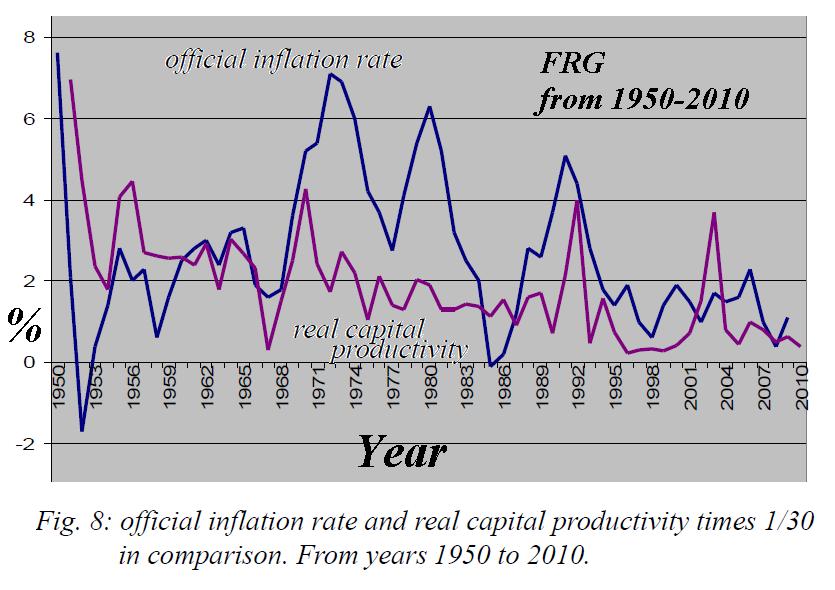

Let us now examine the official

inflation rate, which was determined by the Federal Statistical Office, in comparison

to the capital productivity, where the constant factor![]() was

chosen: In Figure 8 you can see the amazing parallel course. An improved

interpolation is therefore possible with an exponential form

was

chosen: In Figure 8 you can see the amazing parallel course. An improved

interpolation is therefore possible with an exponential form

![]() (11.11).

(11.11).

For the FRG a numerical solution results in:

![]() (11.12)

(11.12)

Why do we take for calibration not the official inflation rate? It is not possible because the official inflation rate is only a relatively crude statistical approach to a not yet well understood problem. The official inflation basket varies greatly, and is in the long-term average of about 2.5%. The weightings of the basket of products, that are different for each consumer class and also different in their underlying assumptions, are to be questioned even more critical. As the official inflation rates26 and the subjective impression of the citizen from official numbers differ, recently in the FRG was also the notion of “perceived inflation” introduced, which is determined from other criteria and is significantly higher.

As a final gauge, we can look to us

therefore the ratio![]() which occurs, if we determined it from the official

"average-consumer" basket inflation data. First one notices, that the

official average gradient of 2.5% is too low. Therefore it makes the

unavoidable impression that the inflation rate would be systematically

underestimated. Only when we introduce a constant factor27 of 1.8 we approach the

real values close enough.

which occurs, if we determined it from the official

"average-consumer" basket inflation data. First one notices, that the

official average gradient of 2.5% is too low. Therefore it makes the

unavoidable impression that the inflation rate would be systematically

underestimated. Only when we introduce a constant factor27 of 1.8 we approach the

real values close enough.